Introduction

For the most part, the storage industry has been pretty boring for the past decade. Sure, there have been protocol improvements and capacities have grown wildly. Vendors have come and gone, and new components like SSDs made a splash here and there. From a topology standpoint, though, things have remained mostly status quo--lots of servers pointed to lots of storage devices that are either file or block. Yes, object storage has started to hit the scene, but the solutions that are available to date are really just an alternative "replace this metal box with this other metal box".

In my previous article about flash virtualization, I touched on a few vendors that are taking a new, unique approach to decouple hardware from software. While the concept is not all that new (think Falconstor or Datacore), wide adoption has been limited so far, as interoperability and true heterogeneous integration have always been a concern.

Of course, customers want to free themselves from vendor lock-in, but the reality is that the tier 1 vendors still dominate the ENTERPRISE market. Just look at market share: EMC owns nearly 50 percent of the enterprise NAS market and Netapp sits in second place around the 30 percent range.

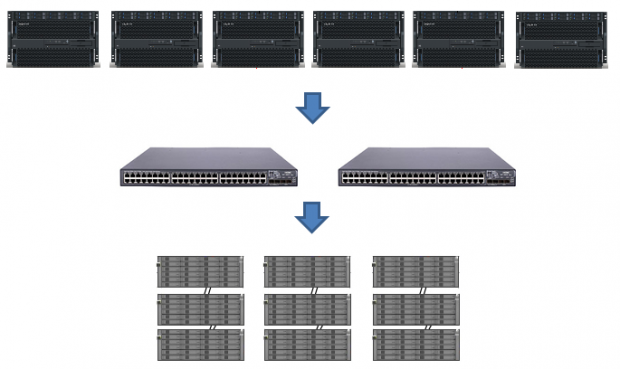

Note the emphasis on the word "enterprise", though. The reason for this emphasis is to clarify that these same vendors have not necessarily fared well in the cloud datacenter environment. It is common knowledge that the Facebooks, Googles, and Amazons of the world have scaled their datacenters by implementing farms of storage servers managed by their own software. Sure, each of the vendors then developed their own version of a cloud-in-a-can to allow enterprises to get a close approximation of this architecture, but the vendor lock-in is still an issue with these solutions. Not to mention, the topology of these solutions are still in the legacy frame of mind of many servers pointed to many storage arrays, as illustrated here.

The market is about to see a major shift in this mindset, though, as several new solutions around software-defined storage are hitting the market. The big difference now is that it is not just a few new venture backed start-ups here and there. This time, the big boys are getting in the game, with the most notable entrant being VMware with the upcoming release of VSAN.

What is VSAN?

This week, VMware is set to announce the availability of their much-anticipated VSAN software-defined storage solution. While they have not made the launch official yet, it can be assumed they are announcing availability since their March 6 webinar on the topic of VSAN is being hosted by the CEO and they previously reported VSAN availability in Q1. The product has been in beta for some time now and there are a reported 10,000 downloads having already taken place; however, there still seems to be a bit of confusion about what exactly VSAN is or what it is not. To clarify, let us start by looking at what it is not.

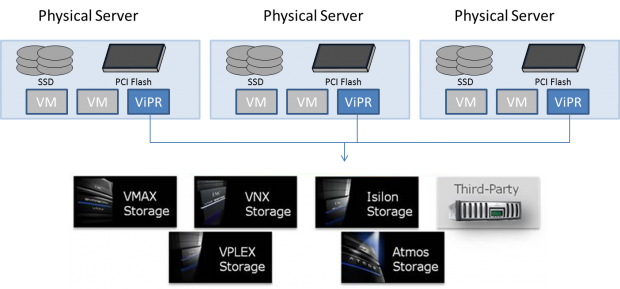

Probably the most common misconception people make about VSAN is comparing it to EMC's ViPR or Netapp's FlexArray products. While there is similarity in the concept, and both of these are actually software-defined solutions, there is a very big difference in the implementation and what they accomplish. Without getting into too much granularity, the following image is a high-level representation of how the ViPR product is deployed.

Installed across 3 separate VMs, ViPR sits on top of the hypervisor. It then allows a nice, all-in-one management of external storage devices, including third party vendors.

This is a great solution for simplifying the management of existing storage systems in large enterprises. A typical enterprise already has several different vendors' solutions and having to manage each one separately is cumbersome. A management console like ViPR helps centralize the administration of all these different storage silos, but there is limited, if any, intelligence integrated to the applications or overall virtualized environment. So, in essence, this is still very much born out of the legacy concept covered previously--many servers to many storage systems.

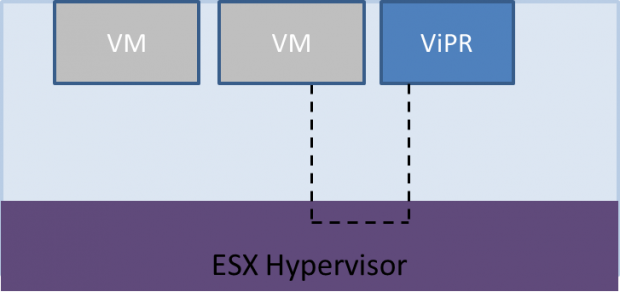

Conceptually, these are both virtual appliances. They sit on top of the hypervisor and attempt to aggregate all of the storage in a virtual pool. From a software layer standpoint, it looks like this:

While this is a simplified look, it illustrates that a virtual appliance sits outside the actual hypervisor. This is important to highlight because it means that ViPR is not actually in the hypervisor itself and, thus, has limited view of what takes place there. ViPR has knowledge of the storage pools it manages, but not the overall virtualized datacenter. This is where the convergence of the software-defined datacenter and, more specifically, the introduction of VSAN separates itself.

Final Thoughts

Provided directly from VMware, this image illustrates the integration of VSAN into the actual vCenter stack. Notice in this image that VMs actually sit on top of vSphere and VSAN, not next to them. Also, note that there are no silos of storage vendors below the vCenter servers. The fact is each of the servers is a storage device.

I repeat: there are no silos of storage below the vCenter servers. The servers ARE the storage. Tiering, snapshots, and all of the policies are configured and managed within vSphere.

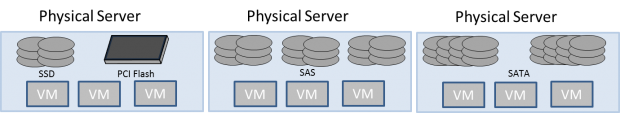

Because of this, a customer is now able to select off-the-shelf servers and even the components in them, such as which drive or flash accelerator. That is, of course, as long as it is selected from a compatibility list provided by VMware. A sample integrated solution looks like this:

In this sample configuration, there are three separate physical servers that have a variety of drives implemented in each providing three tiers of storage: SSD, SAS, and SATA. All three physical servers would be part of a vCenter Server where all of the storage would be pooled and managed by VSAN. When it comes time to expand, the customer has flexibility to select the next best configuration that matches their budget, risk, and performance requirements.

According to early information out of VMware, this will scale to 16 nodes that can support up to 35 drives each (in addition to five SSDs or PCI-e flash devices). With SATA drives now available in 4TB capacities, that comes out to over 2PB in a single cluster.

The cost savings of this could be astronomical. Of course, it will depend greatly on what the licensing cost for VSAN is. Sure, a customer can save a ton of money buying off-the-shelf equipment, but the value would be greatly negated if there were high licensing fees from VMware.

Aside from costs savings, though, there is the added benefit of having the intelligence built right into the stack. The shared visibility between compute, application, and storage is a large step forward to a true software-defined datacenter. Instead of having to pre-configure LUNs and then presenting them to applications to be consumed, applications will be able to consume storage on an as-needed basis. In the big datacenter world of dynamic workloads, that is a tremendous benefit from a performance and cost perspective. This will become an even bigger story as VMware eventually integrates their software-defined network technology from the Nicira acquisition.

One final thought: Where other vendors have attempted to be the magical intermediary that freed the software management piece from the hardware, VMware has one gigantic advantage: they already have a very sizeable install base and a mass of users that know how to use their products. They have the partnerships in place for both interoperability and integration at customer sites.

If the technology holds up and the licensing fees are attractive, it is quite possible VMware could be in a position to turn the storage industry on its head.

United

States: Find other tech and computer products like this

over at

United

States: Find other tech and computer products like this

over at  United

Kingdom: Find other tech and computer products like this

over at

United

Kingdom: Find other tech and computer products like this

over at  Australia:

Find other tech and computer products like this over at

Australia:

Find other tech and computer products like this over at  Canada:

Find other tech and computer products like this over at

Canada:

Find other tech and computer products like this over at  Deutschland:

Finde andere Technik- und Computerprodukte wie dieses auf

Deutschland:

Finde andere Technik- und Computerprodukte wie dieses auf